Finding disc edema on one of your patients presents clinical challenges on its own, but this is exacerbated even further when you have a pediatric patient to manage. Although pediatric disc edema is less common than in adults, every provider should have a well-established plan of action to address any possible cases that are in their chair. Disc edema can be due to both life and sight threatening conditions and must be handled swiftly.

Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve. This can be anterior (papillitis) or this can be posterior to the globe (retrobulbar). Papillitis is more common in pediatric patients. Pediatric optic neuritis is quite rare at about 10% of the adult rate. Typically presenting symptoms aid in the diagnosis of neuritis, but getting reliable symptom reports from a pediatric patient can be challenging. Common symptoms include decreased vision, pain with eye movement, changes in color vision or decrease in brightness. A relative afferent pupillary defect is often present as well if the case is unilateral. Pediatric optic neuritis tends to be more often bilateral with more severe visual decrease than adults. Post-infectious optic neuritis is more common than demyelinating causes for pediatric patients. Vaccinations have been rarely found to cause optic neuritis, with the diseases themselves coming with a higher risk of optic neuritis than the vaccines. Upon a literature review, there are no cases of the COVID vaccine causing optic neuritis to date. There are rare reports of COVID infected patients developing neuritis.

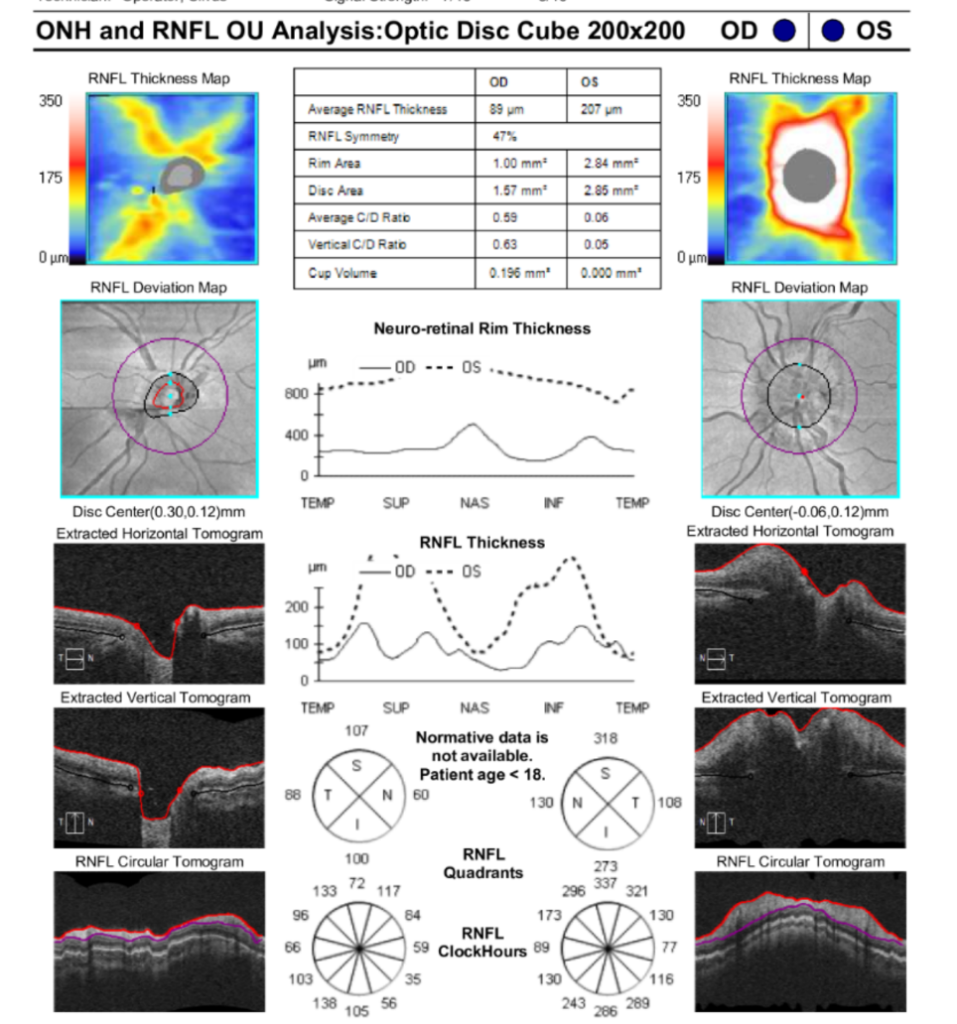

Figure 1: Pediatric patient with OS optic neuritis, initial evaluation.

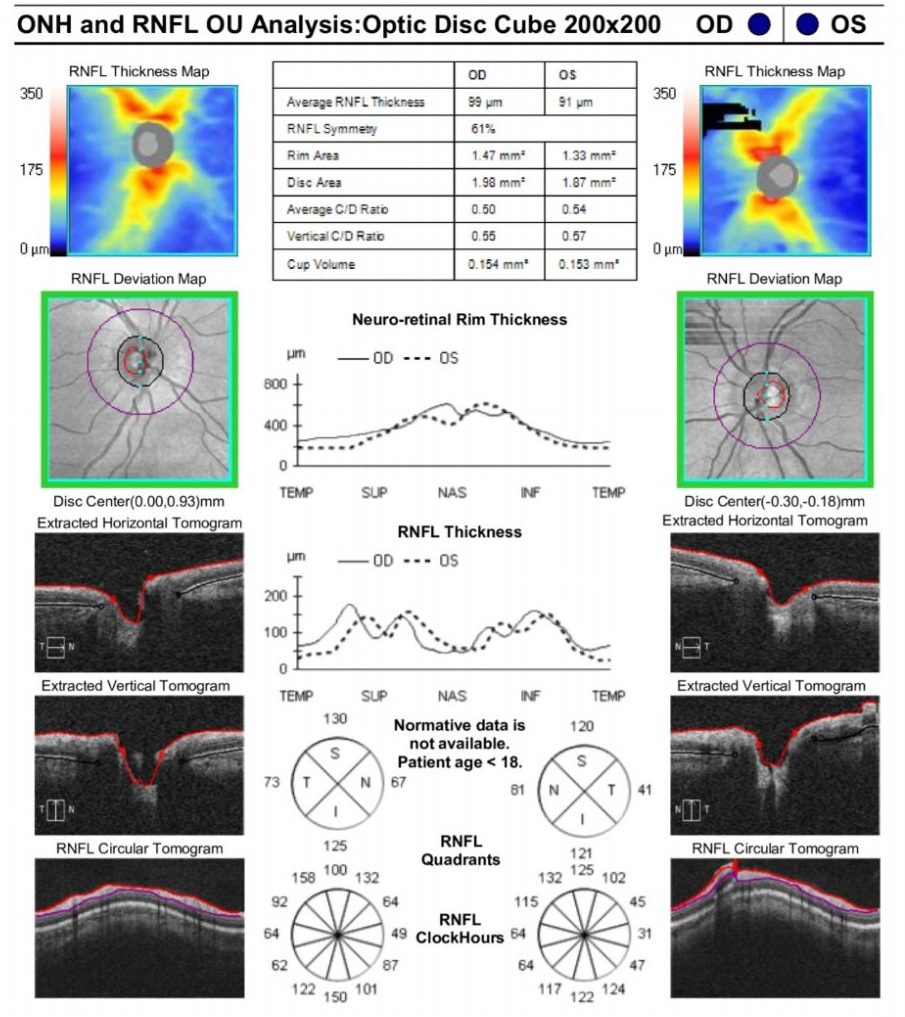

Figure 2: Same pediatric patient as figure 1 after IV and oral steroid treatment.

Papilledema is optic disc swelling due to elevated intracranial pressure. Causative factors are diverse, but can include life-threatening conditions such as compressive lesions, meningitis or subdural or subarachnoid hemorrhaging. Papilledema can present with a wide variety of symptoms. The patient may be asymptomatic or complain of headaches, dizziness, vomiting and nausea. Another symptom is pulsatile tinnitus or a rhythmic whooshing sound experienced by patients. The patient may report vision loss, diplopia, color changes or transient visual obscurations, but these visual symptoms tend to present later than in other disc edema cases. For pediatric patients with vomiting, nausea and/or headaches, the additional finding of papilledema has been found to strongly correlate with hydrocephalus due to a primary brain tumor.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension or pseudotumor cerebri can also cause papilledema. In pre-pubescent patients, body mass is much less of a causative factor than in post-pubescent patients as is female gender. Renal disease, anemia, hormone imbalance, steroid treatment, medications, dural sinus thrombosis and more can cause idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

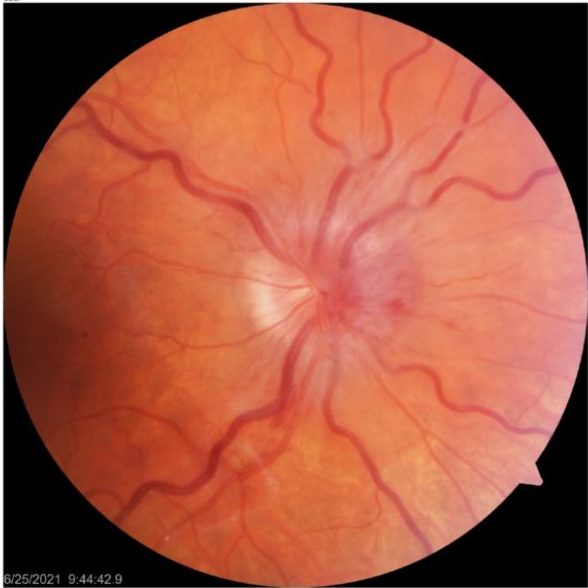

Figure 3: Unilateral disc edema with hemorrhaging and vascular changes.

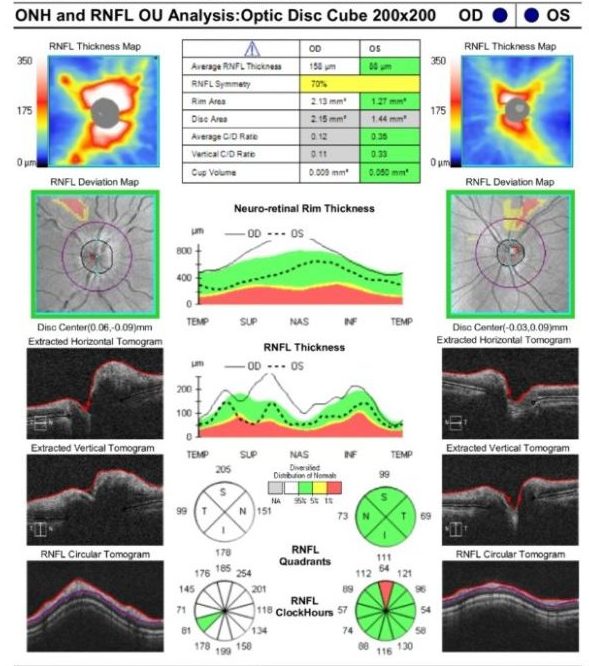

Figure 4: RNFL of figure 3 patient demonstrating disc edema OD.

Pseudopapilledema is when the optic nerves falsely appear swollen due to varying factors such as disc drusen, tilted nerves, crowded or hypoplastic nerves. One review paper mentions that 75% of pediatric patients referred for papilledema were found to have pseudopapilledema.

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) is an ischemic infarction of the anterior optic nerve. AION is exceptionally rare in patients younger than 50. There are rare case reports in pediatric patients undergoing continuous peritoneal dialysis or undergoing major surgical procedures that have experienced non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy due to chronic hypotension. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, hypotension or the lack of a kidney creates higher risks for dialysis induced AION in pediatrics.

Variable other factors can create disc edema including hereditary conditions (Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, dominant optic atrophy, recessive optic atrophy, x-linked optic atrophy), infectious conditions (tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, toxocariasis, Lyme disease), non-infectious (sarcoid, lupus), nutritional (vitamin B or folic acid deficiencies), toxic (ethambutol, lead, arsenic and many others) or ocular (pars planitis).

The list of differential diagnosis for disc edema is vast. Finding the causative factor is imperative. Life-threatening and sight-threatening conditions must be identified and proper treatment initiated as swiftly as possible. Neuroimaging is an important step. MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast is often recommended. MRV may also be indicated to assess venous anatomy. For papilledema, a lumbar puncture, after MRI results have been obtained, may be indicated to determine opening pressure and cerebrospinal fluid composition. Keep in mind that when ordering neuroimaging and lumbar puncture for pediatrics, it is not the same as ordering for your adult patients. Many radiology centers do not perform imaging on pediatric patients. Often, pediatric patients must have anesthesia in order to undergo these evaluations. Be sure to call your local radiology departments. Some will attempt imaging without anesthesia, but many will not. In Northwest Washington, our pediatric patients are typically sent to Seattle Children’s Hospital for neuroimaging and/or lumbar punctures.

Remember to take time to be empathetic and compassionate towards your pediatric patient and their guardians. Finding disc edema in a young patient can be scary, especially considering the numerous differential diagnoses of varying severity. Take time to explain your findings and your plan. If you are not personally comfortable ordering further testing, send them to a pediatric specialist. Be sure to call ahead to either set-up a stat appointment or to alert the ER department at a children’s hospital what patient is on the way and why.

References:

Al-Kaabi, Abdullah, et al. Bilateral Anterior Ischaemic Optic Neuropathy in a Child on Continuous Peritoneal Dialysis. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. November 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5135466/

Allen, Evan, et al. The Clinical and Radiological Evaluation of Primary Brain Tumors in Children, Part I: Clinical Evaluation. Journal of the National Medical Association, Vol 85, No 6. 1993. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2571872/pdf/jnma00281-0043.pdf

Dufek, Stephanie, et al. Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in Pediatric Peritoneal Dialysis: Risk Factors and Therapy. Pediatric Nephrology. 2014. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24488506/

Gupta, Divakar, et al. Traumatic Optic Neuropathy. American Academy of Ophthalmology, EyeWiki. May 2021. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Traumatic_Optic_Neuropathy

Hobbs, Brianne and Osmotherly, Kaila. Long-term Follow-up of Suspected Vaccine-Induced Papillitis: A Teaching Case Report. Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry. Vol 41, num 2, 2016. https://journal.opted.org/article/long-term-follow-up-of-suspected-vaccine-induced-papillitis-a-teaching-case-report/

Kaiser, Peter and Friedman, Neil. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary: Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. Fourth Edition. 2014 Elesevier.

Kanonidou, Evgenia, et al. Unilateral Optic Disc Edema in a Paediatric Patient: Diagnostic Dilemmas and Management. Hindawi. December 2010. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/crim/2010/529081/

Mancha, Saoul, et al. With Disc Edemas, Act Fast. Review of Optometry. March 2020. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/with-disc-edemas-act-fast

McCafferty, Brandon, et al. The Diagnostic Challenge of Evaluating Papilledema in the Pediatric Patient. Taiwan Journal of Ophthalmology. March 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5525598/

McDowell, Paula and Williamson, Alexandra. Vaccines and Vulnerable Eyes: What to Look For. Review of Optometry. 15 March 2021. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/vaccines-and-vulnerable-eyes-what-to-look-for

Peragallo, Jason. How to Manage Pediatric Optic Neuritis. Review of Ophthalmology. April 2018. https://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/article/how-to-manage-pediatric-optic-neuritis

Rigi, Mohammed, et al. Papilledema: Epidemiology, Etiology and Clinical Management. Dovepress Eye and Brain. August 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5398730/

Ubhi, Pavanjeet, et al. Discern Optic Nerve Head Drusen from True Papilledema. Review of Optometry. December 2015. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/discern-optic-nerve-head-drusen-from-true-papilledema

Weiner, Gabrielle. Case Studies of Disc Edema. American Academy of Ophthalmology. October 2015. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/case-studies-of-optic-disc-edema#Quick

Author: Leigh M. Gongaware, OD, MS

Specialties: Medical Eye Care

Working with Dr. Ingrid Carlson and pediatric patients continues to be rewarding and fulfilling. I enjoy asking kids about their hobbies and vacations, you hear about all kinds of things this way. I also enjoy letting kids take a look at someone’s eye in the slit lamp, they think it’s either great or super gross!