Pediatric Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis

Pediatric blepharokeratoconjunctivitis (BKC) winds up in my chair way more than I would have predicted when I left optometry school. Our clinic sees this so much, we even have a drop-down phrase in our electronic record system for diagnosis and plan that we can adjust. This condition is a chronic inflammatory disease stemming from lid margin inflammation leading to ocular surface disease. BKC comes with a wide array of symptoms and clinical signs. Pediatric BKC can lead to vision threatening complications if not treated promptly and properly.

Symptoms of BKC are varying in type and intensity. I have had BKC patients referred by pediatricians for chronic red eyes or decreased vision and referred by comanaging optometrists for difficult exams due to extreme photophobia. Patients or parents may note recurrent chalazia/styes, ocular irritation, chronic redness and tearing, blurry vision, chronic eye rubbing and extreme light sensitivity.

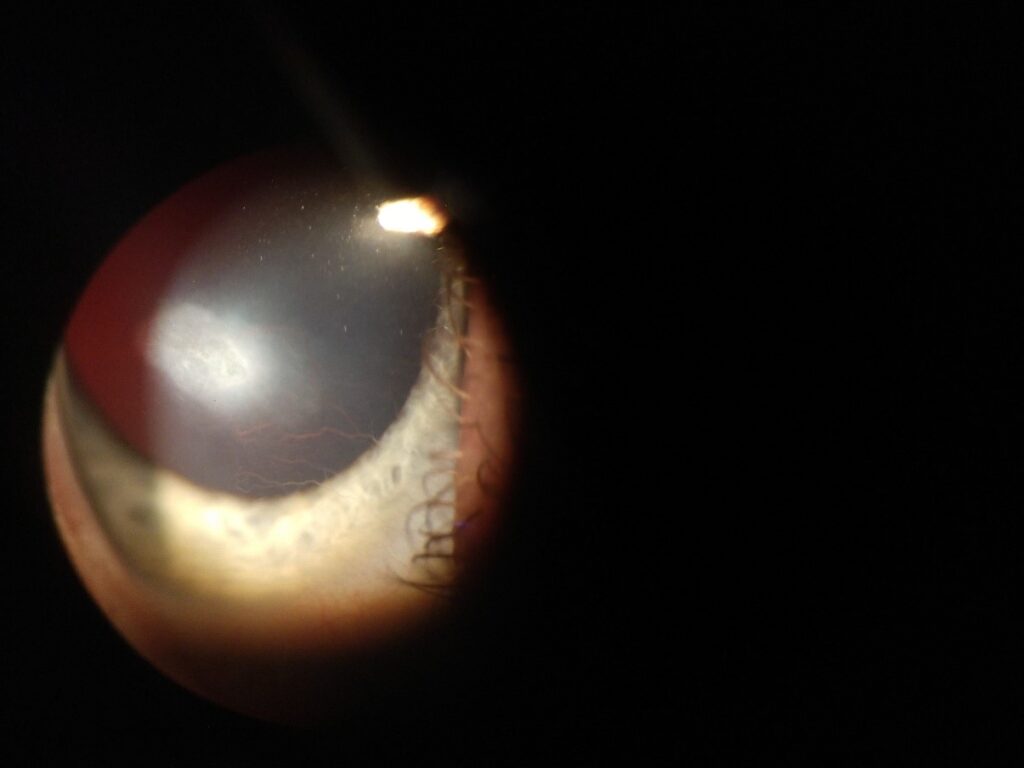

Clinical signs of BKC are often bilateral, though potentially asymmetric. Signs include anterior and/or posterior blepharitis, phlyctenular conjunctivitis, conjunctival hyperemia or chemosis, corneal neovascularization, punctate keratitis, pannus, edema, peripheral corneal thinning/scarring. I also routinely see concurrent lagophthalmos in my pediatric BKC patients.

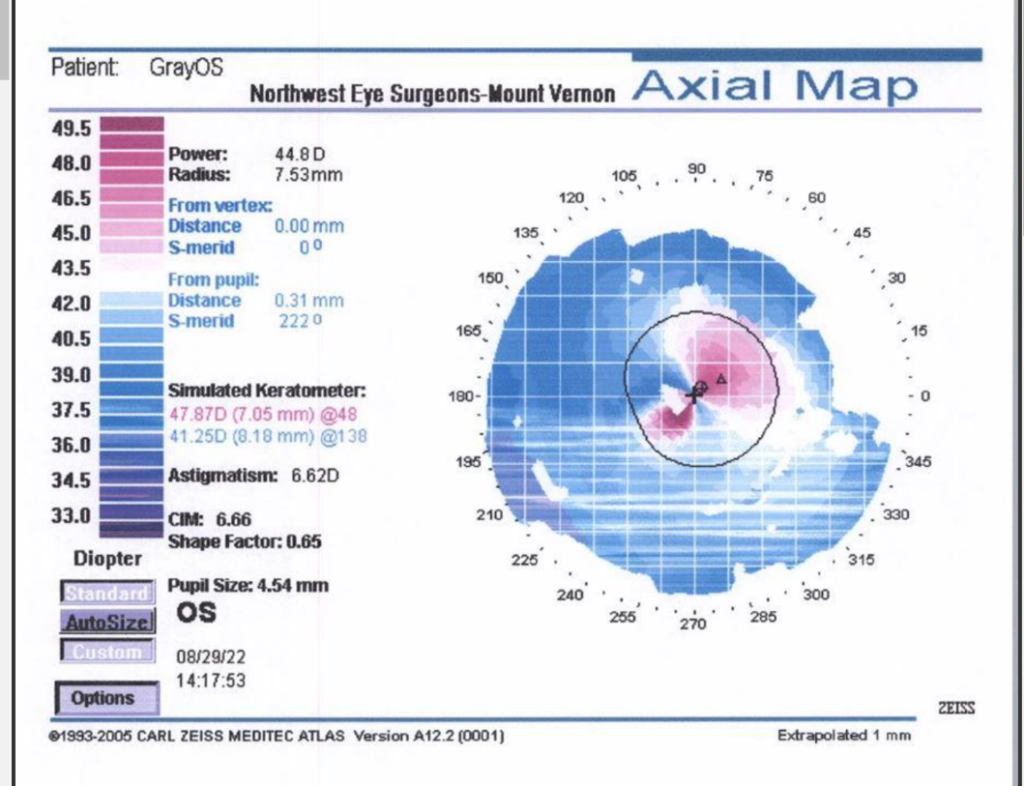

Studies have noted more frequent and more severe corneal involvement for pediatric patients as opposed to adult BKC patients. In addition, pediatric patients that are diagnosed at an older age are more at risk for corneal involvement. Often, corneal thinning and scarring will start peripheral, but can spread centrally in severe or untreated cases. This can lead to decreased visual potential and/or irregular astigmatism.

|

|

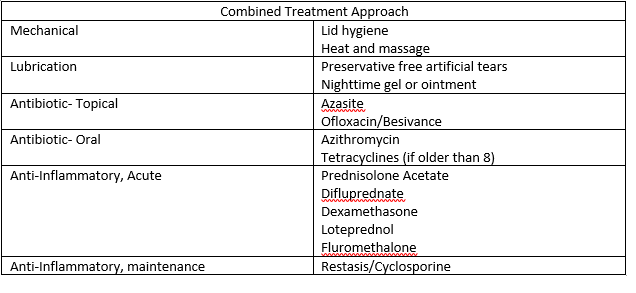

I often describe BKC as a cascading series of events that is triggered by lid disease. It is important that both patients and guardians understand the importance of proper lid hygiene and maintenance therapy ongoing. Treatment must be a combined approach of mechanical, lubricating, antibiotic, and anti-inflammatory techniques. Providers must be sure to stress the importance of lid hygiene and discuss techniques in depth. I will often provide samples of lid scrubs or sprays. Warm compresses are also essential. I highly recommend microwavable or electronic eye masks. Devices such as iLux and Lipiflow are great options, though often cost prohibitive. Severe cases may require systemic immunosuppression or even steroidal injections.

My goal is to get patients on a maintenance therapy approach of daily lid hygiene, daily warm compresses, artificial tears at least twice per day (nighttime gel or ointment with lagophthalmos) and Cyclosporine twice per day. I try to limit the extended use of steroids as much as possible. Some patients do require ongoing lose dose or gentle steroids and must be monitored for any development of a steroid response or cataract formation.

BKC requires ongoing monitoring and treatment. Patients will often grow out of pediatric BKC before adulthood, but not in every case. BKC can be a frustrating condition to manage, but seeing a pediatric patient finally have comfortable eyes and be able to see is always rewarding.

Lee Gongaware, OD

Specialty: Medical Eye Care

I decided to write about BKC due to the number of pediatric BKC patients that I see and how drastically this condition can change a child’s future visual potential when managed properly or not. I enjoy continuing to see a wide variety of medical optometry patients of all ages. At Northwest Eye Surgeons, I value working on a team of providers with unique specialties that can come together to treat patients.

Sources

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis (BKC) of Childhood. EyeWiki. March 2022. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis_(BKC)_of_Childhood

American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Care Online. Tetracycline (Systemic). https://publications.aap.org/pediatriccare/drug-monograph/18/5383/Tetracycline-Systemic

Daniel, Moritz Claudius, et al. Challenges in the Management of Pediatric Blephrokeratoconjunctivitis / Ocular Rosacea. Expert Review of Ophthalmology, 11:4, 299-309. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17469899.2016.1209408

Rodriguez-Garcia, A., et al. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis in childhood: corneal involvement and visual outcome. Eye 30, 438-446. March 2016. https://www.nature.com/articles/eye2015249

Sabeti, Saama, et al. Management of meibomian gland dysfunction: a review. Elsevier: ScienceDirect. January 2019. https://www.nueyecal.com/files/teaching-schedule/article%202-1619577119.pdf