With the widespread adoption of clear corneal incisions during routine cataract surgery, little post-operative bleeding is expected during follow-up. However, when hyphema or bleeding into the anterior chamber is seen post-operatively it must be managed appropriately to minimize morbidity and promote visual recovery. The following article summarizes the causes of post-operative hyphema, suggests an approach to treating it and outlines when a referral back to the surgeon is prudent.

Suspended red blood cells (microhyphema) or heme staining along the wound may be sourced from microtrauma to the highly vascularized iris during surgery. This is especially true should iris hooks, pupillary expansion rings or other iris manipulation be required during surgery.

If cataract surgery is combined with a glaucoma procedure this increases the risk of hyphema. Ab interno combined procedures such as trabeculotomy with Kahook Dual blade or gonioscopy assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT) create a direct connection between the anterior chamber and Schlem’s canal. A certain amount of bleeding is expected in these procedures as significant trauma to the trabeculum occurs.1 Even the comparatively less invasive iStent (titanium microbypass stent) embedded into Schlem’s cannal will allow blood to reflux back into the chamber should episcleral venous pressure (EVP) be temporarily greater than intraocular pressure (IOP).2 This may be the case when pressure to the eye is applied inadvertently during sleep with a pressing hand or pillow causing IOP to increase. When the external pressure is removed, the IOP suddenly drops but EVP remains high allowing blood to reflux into the chamber.3 This exemplifies the importance of wearing an eye shield post-operatively. A patient performing the Valsalva maneuver or similar staining may cause a similar effect by raising EVP and causing reflux. Hyphema may be seen in up to 25% of trabeculectomy cases.4

The risk of hyphema for the above types of glaucoma procedures increases for cases of neovascular glaucoma or when neovascular membranes are found within the anterior segment of the eye.5 Risks of hyphema increase for those with bleeding disorders such as sickle cell anemia, Von Willebrand disease or hemophilia. The risk of hyphema increases as well for those patients on anticoagulants at the time of surgery and convalescence.6 It is noteworthy however, that the current standard of care does not suggest discontinuation of anticoagulants prior to cataract surgery so long as the international normalized ratio (INR) is within therapeutic range.6 ASA should only be discontinued if the benefit outweighs the risk. It should be noted that a 2009 meta-analysis of studies examining the anticoagulant warfarin found that although warfarin use was associated with a 3-fold increase in post-operative bleeding, no bleeding event was associated with permanent vision loss.7

When encountering recurrent hyphema as a late stage complication of cataract surgery keep uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome in your differential. In this syndrome, poorly positioned IOL haptics may chafe the iris, ciliary body or anterior chamber (in the case of an anterior segment IOL). This can cause micro bleeds and chronic inflammation. Look for iris transillumination defects, liberated pigment on the corneal endothelium or IOL and chronic macular edema. UGH syndrome is more common for anterior chamber IOLs or sulcus fixated posterior chamber IOLs of 1-piece design.8

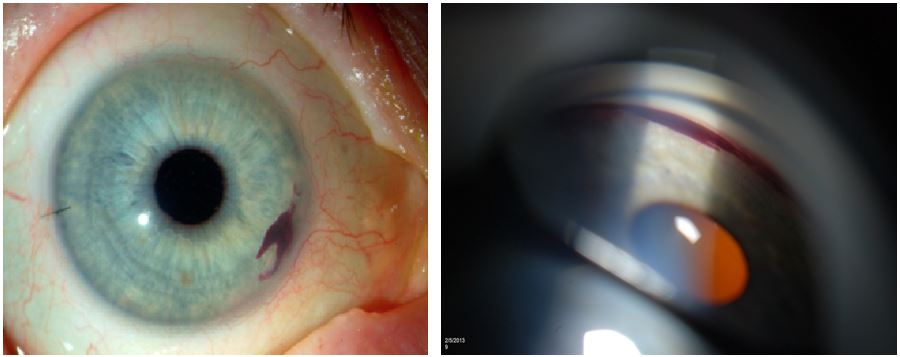

Caption: The figure above left shows small hyphema in an eye after iStent placement. The heme is localized nasally overlying where the iStents were inserted (source Eyeworld.org). Microhyphemas will only be observable by observing the anterior chamber under high magnification with bright illumination. Small amounts of layered heme however are best viewed gonioscopically. The figure above right shows gonioscopic view of the inferior angle where a small amount of heme has collected (source imagebank.asrs.org).

Treatment of hyphema begins with patient education cautioning that activity should be restricted and a clear shield should be worn to avoid touching or rubbing the eye. The head should remain elevated at least 45 degrees even during sleep, so as to allow blood to settle in the anterior chamber. Patients should be reminded to avoid ASA or NSAID analgesics if possible as these medications have anticoagulant properties that increase the risk of a re-bleed. Potent topical steroids such as difluprednate 0.05% (Durezol) or prednisolone acetate 1.0% (Pred Forte) should be prescribed for associated inflammation. Cycloplegics such as atropine 1.0% or cyclopentolate 1.0% can be prescribed if patients have ciliary spasm or are photophobic. Associated ocular hypertension should be managed aggressively using aqueous suppressants such as topical beta blockers and/or alpha agonists. If necessary topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as dorzolamide or oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide can be used however these should be avoided if sickle cell disease is suspected. In such patients, their use topically can promote erythrocytic sickling within the chamber; their use orally can promote a sickling crisis.

Although complete hyphemas (where the entire chamber is filled with blood) are rare in the setting of routine surgery, I suggest alerting the surgeon should they occur. Classical teaching states that if the intraocular pressure remains >25 for >5 days in the setting of a complete hyphema, corneal blood staining and its associated vision loss is possible.9,10 Previous studies with traumatic hyphema have revealed that failure to clear past 50% within a week is associated with peripheral anterior synechiae.11 If the intraocular pressure cannot be adequately controlled, concern for glaucomatous optic atrophy increases and this should prompt a call to the surgeon. The majority of post-operative hyphemas however are small, can be managed medically and are expected to clear over several days. In such patients, remaining vigilant while medically managing inflammation and intraocular pressure is appropriate.

References:

- Rahmatnejad K, Pruzan NL, Amanullah S, Shaukat BA, Resende AF, Waisbourd M, Zhan T, Moster MR. Surgical Outcomes of Gonioscopy-assisted Transluminal Trabeculotomy (GATT) in Patients With Open-angle Glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2017 Dec;26(12):1137-1143.

- Sandhu, S., Arora, S., & Edwards, M.C. (2016). A case of delayed onset recurrent hyphema after iStent surgery. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 51(6), e165-e167

- Ahuja, Y., Malihi, M., Sit, A.J. (2012). Delayed onset symptomatic hyphema after ab interno trabeculotomy surgery. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 154(3), 476-480.e2.

- Edmunds, B., Thompson, J. R., Salmon, J. F., & Wormald, R. P. (2002). The National Survey of Trabeculectomy. III. Early and late complications. Eye, 16(3), 297–303.

- Kojima, S., Inatani, M., Shobayashi, K., Haga, A., Inoue, T., & Tanihara, H. (2014). Risk Factors for Hyphema After Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C. Journal of Glaucoma, 23(5), 307–311.

- Grzybowski, A., Kupidura-Majewski, K. Risk of intraocular hemorrhage with oral anticoagulants in ocular surgery. Eye32, 471–472 (2018).

- Jamula E, Anderson J, Douketis JD. Safety of continuing warfarin therapy during cataract surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res 2009; 124: 292–299.

- Zemba M, Camburu G. Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphaema Syndrome. General review.Rom J Ophthalmol. 2017;61(1):11-17

- Walton W, Von Hagen S, Grigorian R, Zarbin M. Management of traumatic hyphema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002 Jul-Aug;47(4):297-334.

- Krauthammer M, Mandelblum J, Spierer O. Corneal Blood Staining after Complicated Cataract Surgery. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep 7;9(3):421-424.

- Read J, Goldberg MF: Comparison of medical treatment for traumatic hyphema. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryn-gol 78:799–815, 1974.

Author: Daniel Nolan, OD

Specialties: Medical Eye Care

Mount Vernon & Bellingham Clinics

As an optometrist working at a surgical center, one of my most important jobs is to coordinate care through referring doctors. Many of our conversations are about post-operative complications, often surrounding new procedures. As our group increasingly performs cataract surgery combined with glaucoma procedures, I thought a targeted review might be helpful to our co-managing doctors. While I enjoy managing a variety of ocular conditions, I can always appreciate the excitement patients have when they experience improved vision from routine cataract surgery.